Creating SVG Images for the Web

SVGs are great for web graphics. They’re small and crisp on any screen and can be modified with CSS and Javascript like any DOM element. Read more on Vector vs. Raster Images for Web in my previous blog post.

What is an SVG?

An SVG stands for “Scalable Vector Graphics”. They’re a web-friendly file format of vector shapes and paths rather than pixel-based (raster) files like PNG, JPG, GIF and WEBP.

If you open an SVG in a text editor, you’d see a series of tags like <path>, <circle>, <rect>, <line>, etc. These elements and their attributes build out SVG shapes which are constrained to the files viewport and can be scaled without losing clarity. Each SVG may also include some inline CSS that defines the style of each element by class, though with some slightly different properties like stroke and fill rather than border and background-color.

SVGs can even include HTML text, which can be handy when creating dynamic graphics.

Creating SVGs

Any vector based application can export or save as SVG. Popular apps include Adobe Illustrator, Adobe XD, Sketch and Figma.

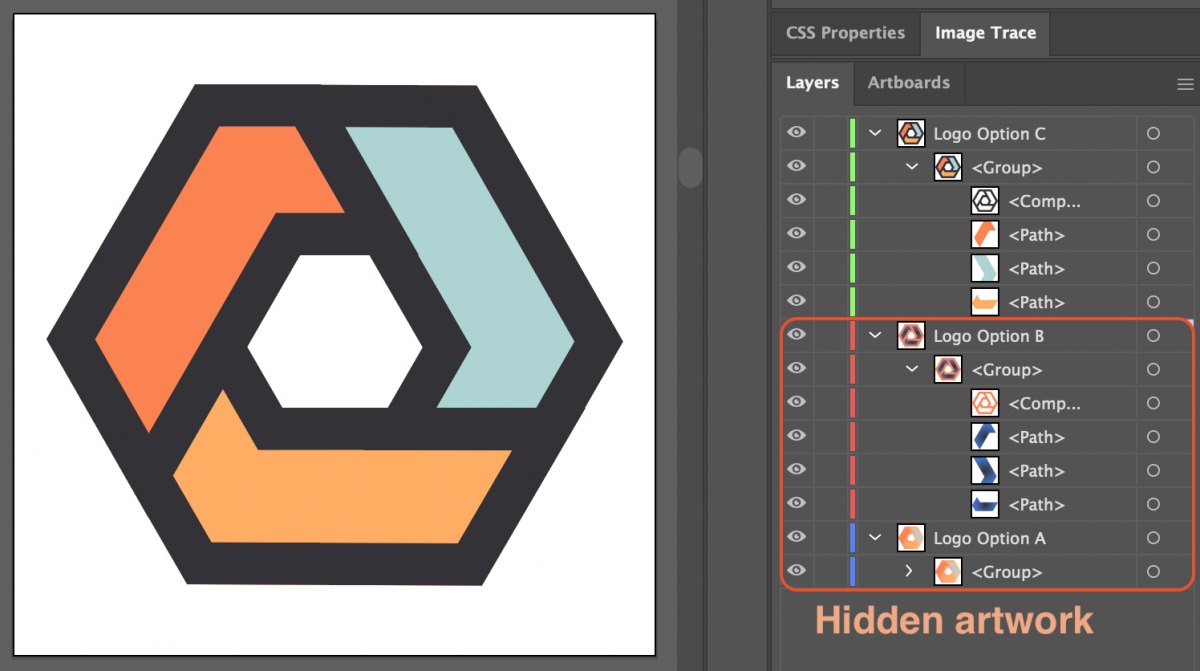

Exporting an SVG is a bit different than exporting a raster file like PNG or JPG. For a raster file, all layers are flattened so that the file only contains information from a single layer. Anything hidden behind the visible layer is stripped out of the source file. SVGs, however, retain information like clip-paths, groups and layers hidden behind others. With an SVG, if you have a circle covering some text, that text still exists within the SVG source even though it may not be visible behind the circle. Since those layers still exist, even if you have two shapes directly on top of each other, a color variation in the lower layer may still appear in the browser.

It’s important that the exported SVG be optimized to include only the information needed in the final file. Extra layers or complex filters or effects may not translate well into the final exported file. Any text that isn’t outlined (eg: turned into shapes) will need to have the applicable web font styles applied to the source SVG’s CSS or added elsewhere. Otherwise, an end user may see default fonts like Times New Roman if they don’t have the font locally.

Firefox requires both viewport and width/height defined in the main SVG tag, else may appear sized incorrectly in a browser, even if the image tag has width and height defined already.

Optimizing an SVG

Though SVGs for graphics can be smaller than their PNG/JPG counterparts, a complex SVG may still end up being quite large. A complex SVG graphic with a lot of paths and shapes can easily be larger than a flattened, web-optimized PNG. Since an SVG is basically a text file with tags and attributes, all that information still takes up bytes, even though it’s just text.

Within a vector application, the designer can simplify objects to use fewer points, merge shapes into a single element rather than groups and use HTML text instead of outlines to reduce an SVGs file size.

SVGs can even be uploaded to WordPress if the theme allows it. Though it would require the following to be added to the beginning of the source if the exported file doesn’t have it already (some apps include it, others don’t):

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

When to use SVG?

Photos and similar artwork will always be best as a raster PNG, JPG or WEBP file. These are pixel-based rather than a set of shapes and paths and should be optimized for the target size. Graphics like logos, graphs and icons are prime candidates for SVGs as they’ll remain sharp and crisp at any size.

All major browsers support SVG images, so there’s few reasons not to use them where applicable.

Making an SVG dynamic

Since an SVG is just markup, it can be added to a website in an tag, or directly in your HTML. When the source is in your markup, any path, group or other SVG object can be overridden with CSS and made interactive with javascript.

For example, in my SVG I might have a path like this:

<path class="obj1" d="M10.6,8.6v9.8h-1V9.5H7.3V8.6H10.6z"/>

I could change the fill with some basic css:

svg .obj1 { fill: #f00; }Or even add some hover effects:

svg .obj1:hover {

fill: #0f0;

cursor: pointer;

}Though there are some differences in CSS attributes and a few quirks, SVG elements are all objects in the DOM and can be manipulated just like any other with javascript for things like click events.

I still remember the old days where using Flash was the only way to make a dynamic header with a custom font without relying on images. With SVG, there’s so much more you can do, and with much better results.